Oops, this is my first newsletter in a while. If you subscribed in recent months — most likely at Wrongcards — then you might have forgotten about me. Don’t panic, this is merely the onset of amnesia, and I respectfully hope it is the good variety of amnesia, in which you slowly realize you’re a government-trained assassin, and not the bad kind that leaves you, say, waking up in an abandoned hotel beside a dead clown, and covered in spiders.

Seasoned subscribers know I can be a bit intermittent with these newsletters. I have this tendency to focus only on a single task, to the exclusion of everything else. I like how I put that; it makes me sound effective and skillful, and not merely bad at multi-tasking. On the other hand, I don’t believe juggling. Juggling is for clowns, and clowns — in my imagination, at least — always wind up dead in abandoned hotel rooms, and I don’t have not the slightest clue why. Is this the sort of thing people talk to therapists about?

But look, writing this newsletter feels wholesome to me. I’m reaching out to a bunch of old friends here. You know what? My ambition is simply to publish these novels, then go off on a book tour around the world and meet many of you in person, and possibly even trick you into buying me tea and cake. I like this ambition. It feels good and right to have ambitions that don’t, in some fashion, involve Nigella Lawson. And I think that if I had a therapist she would agree with me. But I don’t have a therapist — I have you, Reader — though obviously if you happen to know any therapists who look and speak like Nigella Lawson, then it might not be a good thing to let me know.

Excuse me a moment, I was interrupted by Boudica. She came to ask me a question:

“Why hasn’t Byron visited us?”

Boudica is my daughter and Byron is an old friend of mine. I’ve mentioned him several times, I think. He was with me when I was arrested in Germany through no fault of my own. And one time, when my spirit gave out, he killed a giant rat and saved me from a complete nervous breakdown. Oh, and here’s a newsletter from ten years ago, in which I describe how we met. So, as you can see, he’s not a figment of my imagination — although I think he occasionally suspects otherwise.

You see, Byron is an uneasy person. He is unmarried, and has not dated in years, perhaps because he finds women alarming, and possibly because they mostly like to make decisions. Byron, however, does not like to make decisions, and some have said — oh alright, it was me — that he was apparently born without a decision gland.

I have noticed women have a tendency to find him rather handsome and tremendously nice. But inevitably, after talking to him for a little while, they decide he’s a bit too complicated and start wondering which among their friends they can marry him off to, and then Byron’s really in the thick of it. Because there always seems to be this perfectly lovely woman out there who is just coming out of a dreadful marriage, and Byron really should meet her. And so what starts as a polite conversation with one woman turns into Byron going into hiding from two.

Because he gets stressed, you see, when people try to control his life. And the problem is, he has this kindness and earnestness about him that makes women — all women, it seems to me — set about trying to control his life. You … might think I’m exaggerating or something, but I promise you I’m not; it’s an extraordinary phenomenon to witness.

“Why hasn’t Byron visited us?” asked Boudica, who is just turning ten.

“I doubt he has a passport.”

“We should get him a passport,” she says, the wheels already turning in her mind.

I put down my book. “You’re right, we should get him a passport, but it’s a tricky process, and we’ll have to forge some documents. Or perhaps we can ask him to fill out the forms himself. You know how I hate filling out forms.”

“But would he?” asked Boudica.

I think for a moment. “No, he wouldn’t. It’s too much work. Then he’d have to get the tickets. Then, and this is the hard part, get himself to the airport on time.

“That last one is basically the deal-breaker. In the weeks leading up to the flight, he’d a lose a lot of sleep to worry. You see, nobody in Byron’s family has arrived anywhere on time, not in several generations.”

I pause and reflect. “It’s fascinating to observe. If they have to be anywhere at eleven in the morning, they get start getting ready at precisely eleven in the morning. Nobody knows why — not even them. They know they do it, they know it’s a mistake, but they can’t seem to help themselves. Do you know when they wrap their Christmas presents each year? At 10pm on December 25th.”

I shook my head ruefully. “I’ve known that since I met Byron twenty years ago. And for twenty years, I’ve called Byron every Christmas Day at precisely 11pm, just to see how the Christmas wrapping is going.”

“Well, I think we should take control of his life,” says Boudica.

And I think, oh well, here we go again.

Watching Byron make a decision can be an interesting experience. He has a strong aversion to them. Or perhaps he is sensitive to regret, because the possibility of regret is an aspect of most decisions, I seem to think. One time in Boston, we went to lunch and he couldn’t decide what he wanted to eat, so he stared at the menu for forty-five minutes while the rest of us ate and watched him. But this only happened once; he was cross with himself and more decisive in restaurants thereafter. It was the only time I’ve seen him go hungry, because — as I noted in another newsletter — another great mystery surrounding Byron is how often strangers appear out of nowhere and give him food.

The man will never starve, but decisions remain a challenge. All decisions cause him stress because he likes to think everything through thoroughly, which often requires putting matters aside to consider later. But then, the queue starts to get a bit clogged, and inevitably he begins to worry about himself, because … well, when does his family wrap their Christmas presents? Is it all inescapable genetics?

One time, when we were working together at Harvard, I passed him in a hallway. He had that well-honed tragic air, and I could tell he was wondering what, precisely, was wrong with himself.

“Byron,” I explained, passing him, “you are doomed to fatalism.”

He looked at me with despair and said, “Oh god, am I?” . And he shambled away, mumbling under his breath.

But I’m not really making light of the man’s struggles. Frankly, I’ve spent roughly twenty years doing that in front of him, and I consider it a topic about which I am fully expressed. And to be fair, when I think of the word ‘neurotypical’, I somehow do not picture him in my imagination. But my point, I suppose, is that none of us would probably notice this condition if he was married. I asked him once if he thought he’d ever get married, and he told me he couldn’t decide. I told him that one of the reasons people get married is to get out of performing certain chores.

Look at me, I don’t like to fill out forms. Can’t stand forms, but I’m married, so most of the time nobody notices — apart from my wife, I suppose, who has quite-nicely handled all the American-related forms for me. Do you know, I haven’t filed taxes in Australia for two decades? As an Australian citizen, I was supposed to fill out a form annually, stating that I was working overseas and my income was in the United States. It’s a simple two-page form. Well, I didn’t fill it out for eighteen years.

You know what’s worse? I still have to fill out those forms, but I have to backdate them eighteen times. I know this because one day I was feeling on top of things, so I called up the Australian Tax Office to let them know I was back in the country, and they asked me for my Australian Tax Identification Number. I gave it to them, and they said it was lapsed. So I said, well, can you unlapse it? And they said, certainly, but first we have to confirm your identity.

And the nice man at the Australian Tax Office asked me, “Where were you living when you last filed, back in 2002?”

I had no idea. I supplied him with three addresses where I might have stayed, but none of them were correct. We were at an impasse. The man could not confirm my identity.

“Well, I am me,” I assured him. “I can’t imagine anyone else calling you up with the desire to file eighteen — wait, is it twenty now? — forms on my behalf, but the point is … where can we go from here?”

The man thought about it a bit, and then said, “Well, I can send you a form to fill out.”

And you know what? He sent that form and it sat on my desk for a while, and until eventually I threw it away. Because none of the fields made any sense. It’s as if I’m afflicted with a type of dyslexia that only manifests when I’m staring at a form. And anyway, I really can’t remember much about 2002.

So right now, the Australian Tax Office cannot help me and I cannot seem to help them. Do you want to know something astoundingly ridiculous? The only thing I remember about 2002 is that for three months I worked as a temp … at the Australian Tax Office!

Anyway, look — in approximately two weeks, the latest draft of my novel should be sufficiently copy-edited for me to send out to beta readers. If you’d like to be one, reply to this email. (If you’ve already registered your interest, I’ll be contacting you next week). Or, if you’d like to say hello to me for any reason, you may reply to this email. I promised myself I’d tell you something about the new novel(s). It’s difficult to do so, but here I go.

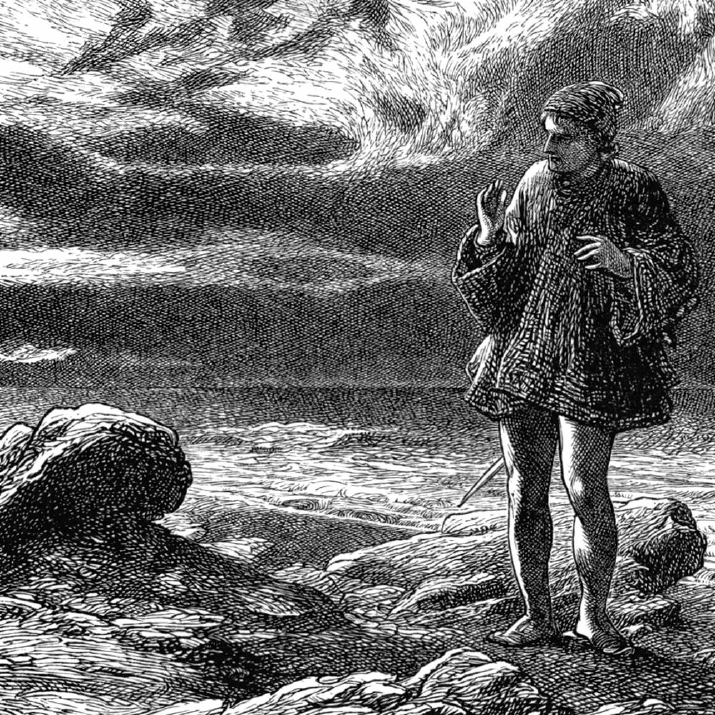

My friends expected me to write something in the vein of Douglas Adams of Terry Pratchet, but what I wrote reminds me somehow of Alexander Dumas. It’s like if The Three Musketeers was set several centuries from now, and upon an exotic planet colonized by Sikhs and Nepalis. I also tried not to be too funny. People often seem to think comedy is hard, but in my experience, being serious is a real trick. There is nothing funny in this entire paragraph, for example, but it’s taken me an hour to write it, and I’m very proud of myself for pulling it off. On the other hand, it took me thirty minutes to write all the preceding paragraphs in this newsletter, so when I say I tried to keep the jokes to a minimum in this novel, that was me suffering for the sake of art. That said, Byron has read it and wants to read it again, and told me there were plenty of funny bits, which I suppose is a good thing, even though it also somehow privately annoys me.

With Chaste Affection,

Kris St. Gabriel