“Oh, the poor Dadda!” Boudicca, who is aged nine, will typically say. Boudicca seems to enjoy referring to me as some sort of third-person object. “Mama didn’t bring him a coffee this morning. How could anyone be so mean to such a handsome Dadda? Don’t worry, Dadda, you and I will run away. You and Mama shall get a divorce, and perhaps my next Mama will be rich, and buy us a swimming pool!”

I rub my jaw, considering. Admittedly, a swimming pool would be a nice addition to my life. But as I mentioned a moment ago, whenever my progeny raises the subject of my general handsomeness, trouble is usually afoot.

“Where is your sister?” I ask warily.

Hattie, aged seven, wafts into the room in a cloud of agitation. Then her brow is pressed against mine.

“Dadda,” she asks, cupping my chin in her tiny hands, “am I loved?”

“You are,” I admit, becoming alert and business-like. “So, you might as well confess, I suppose. What have you done?”

“Hattie has been vexing Mama,” explains her older sister, her admiration for her sister plainly obvious.

“And Boudicca,” Hattie says, “is not being a wonderful sibling.”

“How could you say such a terrible thing, Hattie?” declaims Boudicca with delight. “But let’s leave the poor, handsome Dadda alone – he’s trying to write a book!”

“Wait,” I say, succumbing to the interruption. “Why is your mama vexed?”

“It’s nothing, Dadda. Just a seahorse.”

I nod and pretend this answer makes sense to me. Then a thought occurs. “Is this something to do with Boomshaka?”

They shake their heads, and I relax. If it has nothing to do with Boomshaka then I’ll probably be able to cope with it. Frankly, I’m done with Boomshaka. And Boomshaka, in case you want to know, is a completely made-up god whom I invented as a sort of thought-experiment. I was trying to teach my girls a bit about religion because they were asking questions. Why is Uncle Baldev a Sikh? What is a Sikh? And how is it different from Uncle Andy, etcetera?

The latter is a Jewish jazz musician from Long Island. They have somehow adopted several uncles and aunts from among my various friends. It’s my fault, I suppose. I am naturally gregarious and far too charming.

“It’s often better not to talk about religion,” I tell the girls. And remembering the various Christianity-themed Wrongcards I created years ago, I add, “Or people will get upset and write you letters.”

Which is unfair, frankly. My right to not take religion seriously is practically god given, and comes from my mother’s side of the family. My Great Grandfather was an (Irish) policeman in Sydney. He was Roman Catholic, and thus (obviously) gave me about a dozen great uncles and aunts. One day, he had the local priest over for Sunday dinner, and at some point the priest looked at all those children – among which was my grandfather, of course– and calmly explained that, though the children’s parents were married, the mother was a protestant. Therefore, he explained, they were all technically illegitimate.

“In other words,” as I summarized to Hattie and Boudicca one evening, “the children – my grandfather, for instance – were going to burn in hell forever. Now, this happened in the Nineteen Twenties. As you’re aware, your father’s side of the family descends almost entirely from Irish immigrants.

“Which means,” I added, scowling, “we never forget.”

Hattie already looked angry at this priest. I sighed philosophically. And so, the family tradition continues.

“So what do Christians worship?” asked Boudicca.

“Actually, they worship a jew.”

“Oh, like Uncle Andy!”

Obviously, I can see why other parents do it differently. Worship this one true god, and don’t ask questions! But, you know, because their world is so cosmopolitan, and they have so many uncles, I’m forced to explain religion in fairly general terms. Besides, who has time to offer a comprehensive tour of the subject? I was in the middle of making dinner, after all.

So, I decided to distill all the major themes of the subject into a metaphor. An analogy, if you will. Don’t blame me, it’s what Jesus would have done.

I told my girls the story of a cosmic entity named Boomshaka, and how he spread his teachings far and wide through his prophet (yes, I explained what that was), whose name was Nebuchadnezzar.

“Tell me more of this Nebuchadnezzar person, Dadda,” Hattie interrupted, greatly interested. “I like his name.”

“Well, he’s a very mysterious character, and not much is known about him. Partly because he lived, oh, nine thousand years ago, and also because I have only just now made him up.

“By the way, before we eat a meal, we must bow our heads reverently and say, in a low voice, ‘Woah Boomshaka!’ If we don’t – for, uh, a bunch of nebulous reasons – this divine entity will become enraged and start smiting us. He will smite us with The Rod, The Locust, and The Botch of Egypt, whatever that is, and –”

“This sounds far-fetched,” says seven-year-old Hattie. “In Egypt, they had a god named Amon-Ra, but I know he definitely didn’t exist, because they believed that if you didn’t pray to Amon-Ra, the sun wouldn’t come up. But I haven’t prayed to him ever and the sun still comes up every day, so I know he can’t possibly exist.”

I cannot fault this logic. “Hattie, if everybody could reason half as well as you, there would be far fewer wars.”

But here the tale takes an awkward turn. The thought experiment took on a life of its own. The next day, I overheard Boudicca explain to Hattie that she couldn’t play with a certain doll because it would annoy Boomshaka.

“He would be very cross and send lightning bolts at you!”

“No, he wouldn’t!” replied her little sister. “You haven’t read the holy texts. And I have! Nebuchadnezzar says –”

“Stop!” I exclaimed uneasily. Why had I mentioned the phrase ‘holy texts’? “There are no holy texts! It was a thought experiment. Boomshaka doesn’t exist and –”

Boudicca was scandalized. “How could you say that, Dadda?!”

“He does exist!” Hattie declared, stomping her little foot and waving a finger. “And if you don’t believe in him, you’ll be punished. Frogs will rain from the sky.”

Oh dear, thought I. Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear …

“Now, both of you stop it at once! You’re being unsettling,” I said, apprehensively. “I propose a new family rule. No one is to mention Boomshaka. And if you don’t mind, I’m trying to write a book!”

“He’s persecuting us,” said Boudicca to Hattie, leading her away. I don’t know if she was joking. She’s like me – you can’t always tell.

I used to be like her in a lot of ways. Once upon a time, I didn’t take anything seriously either. Now, unfortunataely, I’m the straight man in my own story. No choice, really. My obligation as parent, is to equip these little girls with all the skills they need to avoid suffering any repercussion from having, ahem, the personalities they inherited from me.

But now I understand the situation a little better, I can see – at a distance – that I created the Cult of Boomshaka that day. I’ve been trying to stomp it out ever since. One time, Hattie caught a fish in the local creek and brought it home in a jar (yes, she’s that kind of child). The next day the fish died, so the girls gave it a little funeral. I was working away, writing a certain, scintillating chapter of my book, when I suddenly heard chanting down the side of the house. Reverent chanting. You know, to Boomshaka.

The next thing I knew, I was running like a fool down the corridor, shouting with hapless vehemence, “Boomshaka doesn’t exist!”

My two little girls were yelling, “Heretic! Unbeliever!” Why did I teach them those words?

If this all sound far-fetched, remember that those uncles I mentioned are subscribed to this newsletter, along with the girls’ cousins, paternal grandfather, and Aunt Zola, etcetera. I wouldn’t get away with much exaggeration. Oh and look – I just received a text message from Boudicca, via her Steam account.

See the nonsense I put up with?

Everything seems to be a hilarious game to those two girls. Perhaps the Boomshaka Phenomenon is a joke, intended to punish their father for some minor infraction involving withheld ice cream. I don’t know! But I will say, I feel strange. It’s as if I have stood at the threshold of something or other, and peered behind the curtain. I have witnessed – and lived through – the accidental creation of a religion. Or, to put it another way, I have seen how one simple, analogous anecdote can be quickly and wilfully misconstrued.

Consider Christianity – once described as one woman’s lie about an affair that got way out of hand. Now there is a religion with all the hallmarks of Bookshaka-ism. I always thought it interesting that Jesus said precisely nothing about gay people, but had lots to say about rich people being unable to enter heaven. Two thousand years later, a Christian can own nineteen investment houses and nobody bats an eyelash. But civil rights for homosexuals? Now there’s a controversial issue!

But don’t listen to me. I’m just someone who accidentally created a religion. So, from a certain point of view, I am the fabled Great Prophet Nebuchadnezzar. Nonetheless – and much like that long-suffering Nazarene – the influence I’ve had on the religion I founded has been suspiciously small.

But now you’re all caught up, I suppose; now you know my I’m so jumpy when my youngest daughter, Hattie, asks questions like:

“Dadda, am I loved?”

I think it took me a full minute to formulate a response. “Hattie, a moment ago you said something about a seahorse.”

“Yes, he’s beautiful. I’m going to put him on the wall in my room.”

“And this seahorse,” I said, with a certain disapprobation, “is he here now, in this room?”

“No, Dadda,” supplies her sister. “I told Hattie to leave him outside.”

So Boudicca has seen this seahorse too, has she? This does not settle my nerves. We live twenty miles inland. There should be no seahorses in the vicinity of my house. What is happening to my life?

“Wait,” I say, with sudden hope. “Are we talking about a toy seahorse?”

Hattie looks at me as if I’m mad. “The seahorse is real, Dadda. It’s just dead.”

“Woah Boomshaka,” intones Boudicca solemnly. I shoot her a warning look.

“Where did the dead seahorse come from?” I ask. And not in an enthusiastic sort of way because – how do small children lay their hands on seahorses this far inland? Now there’s a question I never want answered. “But girls, are we abundantly certain this seahorse is real?”

Hattie’s face is serious. “Yes. Someone was throwing him away, so I decided to keep him.”

Do you see?! Do you see how hard it is for me to get any work done? The conditions in which I have written my latest novel defy all odds. 140,000 words, composed in this environment! I tell you … Boomshaka as my witness, that book is a bloody miracle. And it’s not even the work that’s gives me trouble. It’s not the ideas, or the imagining, or the editing and revising, no … it’s conversations like these! And the fact they occur at regular twelve minute intervals.

Later this year, when you are (I hope) reading my new science fiction novel and finding it (I also hope) wonderful and astonishing, you might find yourself wondering how on Earth does Kris St.Gabriel come up with all these kooky ideas. But that’s the wrong question! The real question is how does he get any work done?

“Alright! You win!” I exclaim, practically flinging my laptop across the room. “My seven-year-old child has found a dead seahorse. Very well! Take me to the seahorse, let’s see it!”

Putting her tiny little hand in mine, Hattie leads me down the corridor and outside, where I find …

Hmmm.

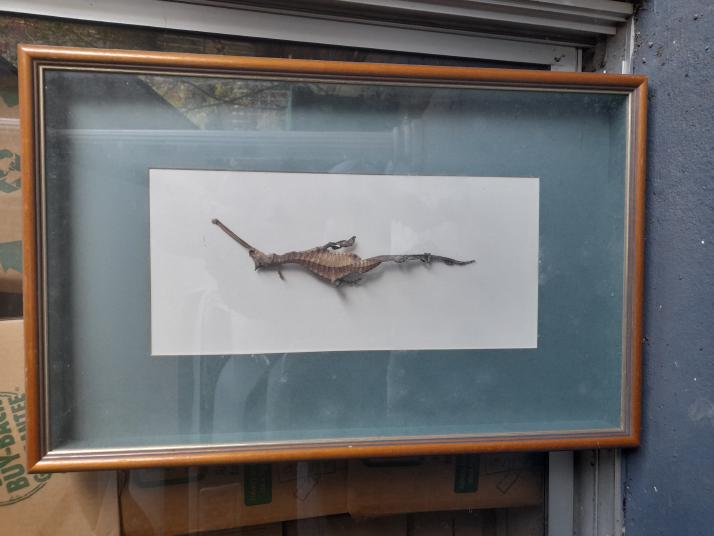

“Hm,” I muse. “It appears somebody has put a dead seahorse inside a picture frame.”

Hattie nods eagerly. “I found it down the street, near some bins. They were throwing it away, if you can believe it.”

“I can believe it, actually. Also, somebody has died, it seems.”

“Woah Boomshaka,” intones Boudicca solemnly, with dancing eyes. I flinch only slightly.

“How do you know somebody died, Dadda?” inquires Hattie, curious as ever. Her father, a practitioner of the subtle art of discernment, stares off into the middle distance.

“Hattie, it is my guess – no, my conviction – that some man found this dead seahorse and put it in a picture frame –”

“Why a man?”

“No woman did this,” I say, nodding at the seahorse with the jaded pathos of a forensic investigator. “No woman would let this thing into her house. This is man’s work. This happens when we’re permitted to decorate. He was obviously a bachelor.” I look at both girls soberly. No wonder their mother is elsewhere, being vexed. I point at the picture frame. “Heed my warning, girls. We men will be fantastic idiots if you let us.”

“Well, I’m a woman, and I think the seahorse looks cool,” says Hattie.

I looked at her sternly. “I humbly submit that it does not. But then, I do not see a seahorse. I see the death of man. And the shimmering, indistinct silhouette of a female relative who has waited a long, long time to throw this picture into the garbage. And girls? I am seized with profound empathy for her.”

They retreat to distant corners of the house – to work great mischief, no doubt. Their father, meanwhile, has retreated to his room to brood.

Teddy Roosevelt – an American president who died about a century ago – had a daughter, Alice, who wore trousers, smoked, and kept a pet snake named Emily Spinach. He left us with this great quote:

“I can do one of two things. I can be President of the United States or I can control Alice Roosevelt. I cannot possibly do both.”

But Teddy Roosevelt, as we know, wrote forty books. That’s right – forty – and all I’m suggesting here is that Hattie and Boudicca could have taught Alice quite a lot.

With chaste affection,

Kris St.Gabriel